It’s been a good while since E3, but with the relaunch of evolve-pr.com, we wanted to publicly release our internal study of the event. This report was written before the ESA data leak, as well as the articles detailing the rumored plans for how E3 would be retooled in the coming years. As such, it does not take either of those things into account as far as discussing the future of the event and how it should be approached. Both of those developments have certainly pushed E3 farther to the edge as far as public opinion and relevance goes, though not in any clearly defined way that invalidates our findings or our conclusions as detailed in this study.

Introduction

E3 has changed a lot over the past few years, and while we have done studies on E3 and other events in the past, things have progressed to the point where another round of study was warranted. Understanding the merits of all industry events is important, yet E3 takes highest precedence with it being among the most expensive events of the year for both industry and press. E3 looks to be facing a major turning point, and we need to watch it carefully to see where things go from here.

There are two major factors that pushed us to do this new round of research: The first is the introduction of a major public presence to the show, which started a few years back but has grown significantly since then. The second factor is that a number of larger companies have been dropping out or otherwise reducing their presence at the show. These factors have fundamentally started to change the nature of E3, away from an all-encompassing industry-focused event, and toward a more public showcase or convention akin to PAX.

Methodology

While we didn’t make the results of our 2017 E3 media study public, we are going to be referencing it here and there in this paper. As such we’ve made every attempt to keep our research methodology and sample composition as close as possible to our prior study so that the results remained comparable. While not directly related, we did produce a similar study that same year covering PAX and GDC, which we did make public, and which is suggested reading for those looking for additional context.

Sample Creation Process & Parameters

Our working sample is comprised of 10% of the attending traditional online media outlets, and 10% of the attending influencers. To gather this working sample we created a larger sample pool by taking both the official media list and the results of our internal E3 2019 user attendance survey which was done via Terminals.io, and stripping them down to meet our parameters. This involved removing any duplicate entries, constraining the list to one person per outlet or channel, and manually checking each entry to ensure that the attached outlet/channel was active within the last two months prior to E3. We also removed any research firms, production companies, and broadcast or print-only outlets from the sample, as they are either untrackable without extensive additional effort, or irrelevant to assessing the larger games media as a whole. While our working influencer sample was drawn completely at random from our sample pool (though in proportion to the platforms within that sample), our working traditional media sample was curated to focus on English-language outlets for ease of data collection, and we made sure we had a spread of outlets representative of a range in traffic numbers for this side of our working sample.

Observations from Sample Creation

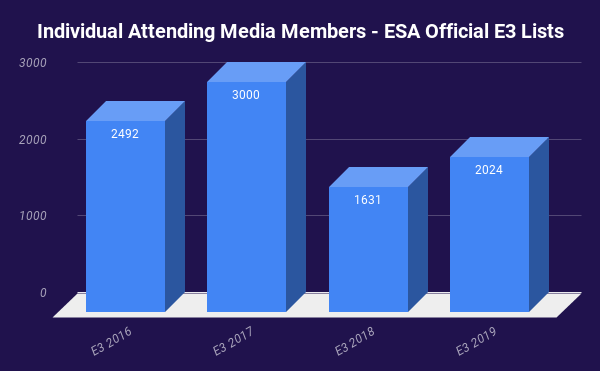

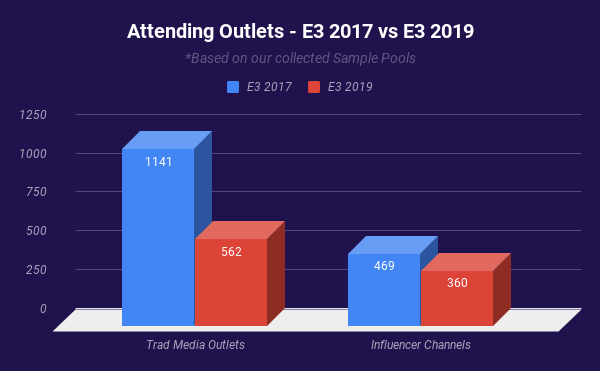

We noticed in building this sample that there was a heavy decrease in the number of outlets and channels attending the event. While the individual number of press/industry members on the ESA’s official media lists have in fact grown since last year, the individual number of qualifying outlets and channels has dropped significantly since our last study, and that is using the same criteria for qualification in both studies. Our traditional media sample in 2017 had 1141 different outlets on it, whereas this round ended up with only 562 outlets, a decrease of ~51%. Our influencer sample in 2017 included 469 qualifying channels, for this round that dropped to 360 channels, a decrease of ~23.5%. For as shocking as these decreases are though, there are a number of factors that could lead to this drop. For instance, we do know that a large number of outlets have shut down in the last two years, which would account for some of the decrease. We also re-classed podcasts into the Influencer sample rather than the Traditional Media sample with this round of study, which would impact the numbers slightly as well. That said, even taking those things into consideration, the cold fact remains that a much smaller number of relevant outlets attended E3 this year as compared to 2017, which of course resulted in less coverage overall.

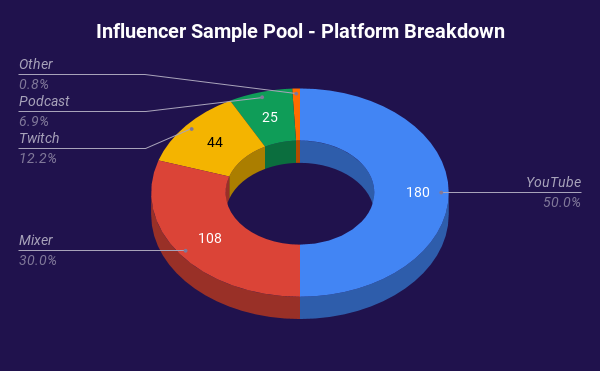

The other interesting trend we noted was the platform distribution of our Influencer sample pool. In past studies (not just of E3, but events in general) we often saw a rough 50/50 split between YouTube and Twitch, with only the odd outlier, which was not the case this year. As shown in the pie chart below, it was YouTube and Mixer that took up the lion’s share of the Influencer media attendance this year, with Twitch and Podcasts having a much smaller (though not statistically insignificant) presence. Whether or not this says anything about the larger cachet and popularity of these platforms remains to be seen, but it does show a shift away from the YouTube/Twitch dichotomy we’ve seen in the past. That said, some of this upset we know results from Microsoft themselves inviting a large number of Mixer streamers to the event, which most certainly helped tip the scales. Even so, that would not account entirely for the margins we’re seeing here.

Margins of Error

As with any study of human behavior there’s plenty of room for error here, and while we’ve done our best to mitigate that we do need to cover what those issues may be. We’ve classed the margins of error for this study under three different headings: Internal, flaws in the data collection; External, flaws that arose from the data itself; and Inherent, flaws arising from the base parameters of the study that are otherwise unavoidable.

Internal

The key issue we ran into here involved variances between the people we had collecting the data for the study. Specifically with three different people collecting coverage data that often demands some degree of subjective analysis, there were naturally going to be slight discrepancies present due to personal interpretation. We did do our best to mitigate these differences through the design of the sheets and tools we used to log the data, and they were accounted for as much as possible during data parsing after the collection was complete. That said these variances do leave some nominal wiggle room on certain coverage statistics and as such bear mentioning.

External

Our data issues stemming from outside sources primarily came down to outlets (especially larger outlets) not being clear or otherwise being misleading with the structure or dates connected to their articles. As with past studies of this sort, we relied heavily on sites tagging their articles as being E3 related and appropriately categorizing their content (e.g. listing a preview as a “Preview” in their system). While this generally works out fine, that was not always the case, as things would get mis-tagged, not tagged until far after publishing, or things categorized as one sort of qualifying content would be a wholly different sort upon reading the text. A more blatant issue we ran into was qualifying articles being republished throughout the study period with new dates, though clearly still being the same article. Our data collectors did make a strong effort to work around these factors by looking for key indicators in the text that would help better categorize things and checking the comments on articles to better ascertain actual publishing dates, but it still leaves some possible room for error here and there.

Inherent

Issues here involved what kind of attendance we were looking at and how long we were looking at things overall. To the former point, that specifically refers to the increased presence of “Gamer Badges” and how that may affect what our sample looked like. While the ESA has stated that they have more media attending than ever before, the fact remains that many members of the press from smaller outlets who were otherwise denied a media badge may have ended up attending using public badges. Aside from the fact that we can’t get access to detailed records for the attending public, we wouldn’t be looking into that group anyways as the core goal was to assess coverage resulting from the event, which the “public” would not be creating. Our survey on Terminals was able to assuage this somewhat, but for as comprehensive as our user base is, it’s not all-encompassing, so we can’t say for sure that we didn’t miss someone in that gap. The other issue we ran into here was the fact that not all coverage resulting from the event would be published within the two week timeframe of the data collection period, meaning our coverage statistics are not as definitive as they could be. To be absolutely frank though, we had to cut off data collection at some point and two weeks makes a lot of sense. Coverage from an event like this loses its worth steadily over time as the zeitgeist moves on and other outlets report the same information. By the time a week has passed after the event, people are already moving on to new releases and talking about Gamescom, so further coverage becomes statistically less worthwhile.

Coverage

As with our past event studies, from this point on we’ll be focusing on just the results from our Traditional Media sample, with a section covering the Influencer sample near the end. This is due to the extreme disparity between the two groups as far as the amount of coverage being produced is concerned.

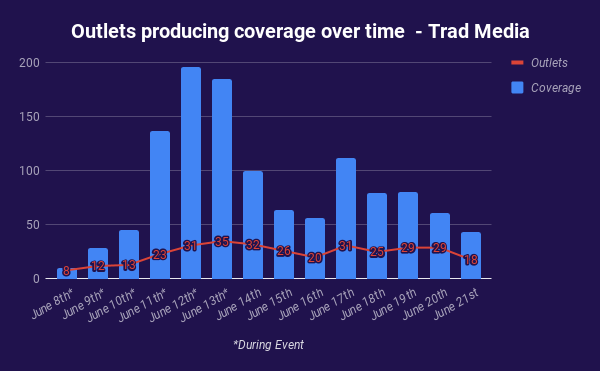

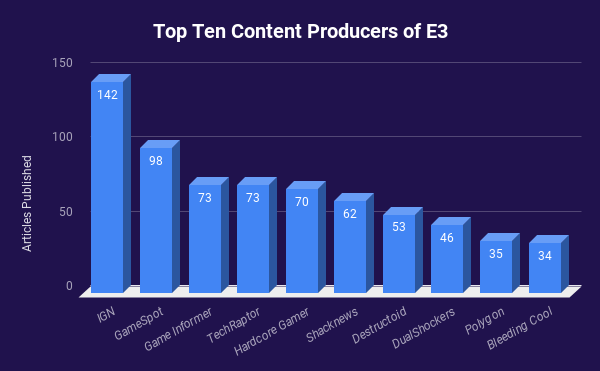

Onto the main event though, our Traditional Media sample produced a total of 1217 qualifying pieces of coverage over the course of the study, which ran from June 8th through till June 21st. For our purposes, a qualifying piece of coverage was anything that was produced with first-hand on the floor knowledge, anything that could be have been reported by someone not at the event was put aside. This round understandably resulted in less coverage than we saw coming back in 2017 (~39.5% less to be specific) but on average we actually saw an increase of 4.2 more qualifying articles coming back per outlet. We also saw that the rough percentage of different outlets covering per day remained consistent with 2017. This is not to say that every outlet was producing content equally though, in fact the skew between the top and bottom ends of the sample is quite vast.

Nearly a quarter of the sample (23.2%) didn’t produce a single qualifying article across the entire study period, and only half (55.4%) managed to put out an average of at least one qualifying article per business day during the study period. The top performers put out far more than that, but that’s mostly due to those outlets having stage shows that were then broken out into a glut of varying articles and videos. On that note, while the top three outlets remained the same as in 2017 (for the reason I just listed), the seven after that changed up dramatically, leaning more towards comparatively smaller though still high end outlets such as Hardcore Gamer and Tech Raptor, who focused more on producing previews and interviews. It’s also worth noting that the lion’s share of coverage from the top ten outlets was published during the show itself rather than in the following week.

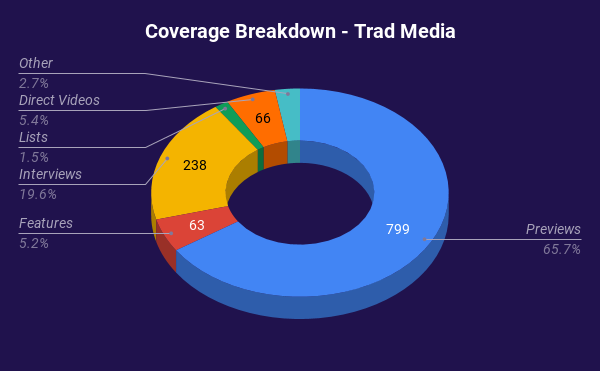

Speaking of the sorts of content produced by these outlets during the show, the spread of content types remained generally consistent with 2017, with the exception of one major change. Specifically the percentage of previews went down while the percentage of interviews went up, both by roughly 5% with some spillover here and there. Whether this can be attributed to outlets wanting to put out more content (an interview arguably takes less time to push out than a preview does) or is maybe just a matter of less games being hands-on at the show is unknown.

Games

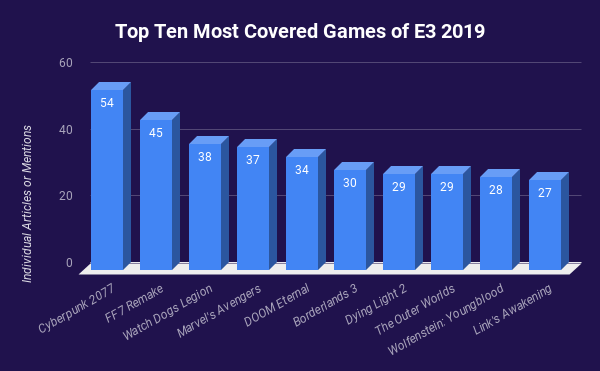

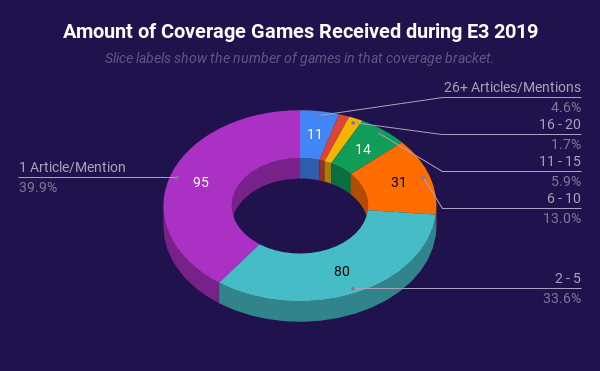

Moving on to the actual games present at E3 and how the coverage broke down along that axis, we come upon a few more interesting revelations. Starting with the top ten games present at the show, we see things level out fairly quickly, with the 6th -10th most covered games receiving roughly equivalent coverage, but nearly half as much as the top most covered title, as compared to 2017 where we saw more a steady drop from 1st to 10th. The larger takeaway though is the fact that of the 240 games we saw covered at the show, ~40% of them received only a singular article or mention. This is ~13% more than in 2017, and if we expand that bottom range to games with 5 articles or less, it becomes 73.5% of the games shown (2019) versus 63.9% (2017), and that’s with there being more games present (or at least covered) during 2017. While only so many conclusions can be drawn from any of the data in this report, I think it’s safe to say we saw the smaller pool of coverage this year really focus in on specific titles.

What puts those particular games into that top echelon of coverage then you ask? A fantastic question, and while the top games are quite varied, there are some connecting threads. Looking at the top 25 most covered games from the show, all but 5 were from established franchises, and of those 5, only 1 wasn’t coming from a well-known developer. This holds true to what we saw from 2017 as well, with similar trends in the top 25 games there. It’s also worth noting that a game doesn’t necessarily have to be well received to be in that top 25; Marvel’s Avengers ended up getting rather tepid previews overall, but took the number 4 slot nonetheless. This means it is likely going to be a game of brand recognition and already established hype when it comes to getting noticed at E3. A larger budget doesn’t hurt either to be sure but there are plenty of larger games that attended which didn’t receive much coverage so there is definitely more to it than just throwing money at the situation.

Influencers

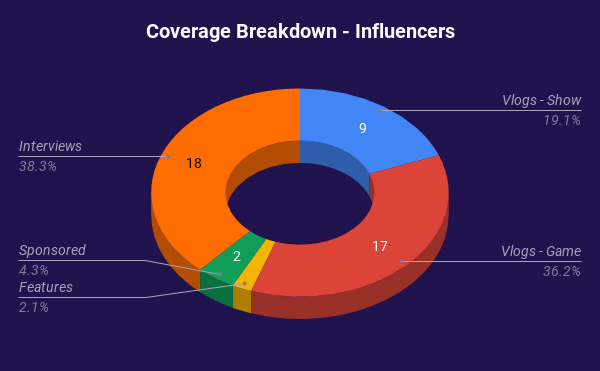

As with previous event studies, we’ve chosen to leave Influencers till last, simply because when it comes to events they’re just not really producing much viable content. Across our Influencer sample of 34 different channels (and a couple of podcasts) we saw only 47 pieces of qualifying coverage. Stacked against the 1217 pieces we saw from the Traditional Media sample, it means those two demographics are hardly comparable and the conclusions drawn from one can’t really be applied to the other. Honestly with so little to work with from this side of the sample, there really isn’t much that can be said beyond that attending Influencers just aren’t creating coverage at E3, at least not in the volume that might be desired.

That said, we did gather some data on that front, so it doesn’t hurt to break that down. Of the 47 pieces of coverage we saw coming back, 18 were interviews, 17 were game related vlogs (essentially previews), and 9 were show related vlogs. Interestingly, only 2 were clearly sponsored content, so for this year at least, paying influencers didn’t really seem to be the key to getting that coverage made. It’s also worth noting that the majority of content went up during the show, with a drastic day by day fall off during the following week. While these are interesting things to note and do shed some light on the possible coverage preferences of influencers, realistically with such a small amount of data we really can’t say anything definitive.

Conclusion

So the cold hard truth is that, in its current state, E3 looks to be in rough shape and is a dicey proposition for a lot of parties. There are plenty of factors influencing this situation, such as the ever increasing public presence, larger names abandoning the event, and the ease of covering the show (or similar presentations) from home. The pool of first-hand coverage that came out of E3 this year has shrunk comparatively, and what remained went even further to those big names, leaving smaller titles high and dry. This results in E3 having lost its identity and failing to excel in any given category; it’s too expensive to be a public focused show like PAX, too crowded and public to be an industry focused event like GDC or DICE, and too broad and loud to generate the undivided attention that larger scale in-house efforts like a Nintendo Direct or even a basic press tour can produce.

There are definitely still cases where attending is useful though. For example, from a networking perspective having someone walking the floor and just establishing contacts is probably helpful (that’s a whole other study though to be honest). Similarly if you’re working with an established franchise and have already built up some decent buzz, chances are you’ll get something out of the event, especially if you’re part of one of the big press conferences that happen before the event proper. The question that needs to be asked though is whether that’s worth the associated cost: paying to fly people out, paying their per diems, paying for accommodations, paying for the booth space, paying for the booth itself, paying for the associated booth costs such as wifi, paying to get merch made, paying to hold some sort of off-site party or meeting, and more. Obviously some of those can be cut or mitigated depending on the sort of presence you want to have at E3 though often at the cost of lesser engagement from press. Even so, doing just the bare minimum at E3 is still very expensive as compared to other North American events, and there are often better ways to spend that money. For small to mid-range companies, I’d advise looking into smaller events instead, especially if you’re looking to show things off to the public rather than the press. For those companies already sitting at the top echelons of the industry, E3 is still useful, but serious discussions need to be had internally about whether it’s more useful than the alternative options that are available, such as the other major shows or setting up your own media event focused solely on your content.

Speaking somewhat personally, I can understand how this can be a hard perspective on E3 to want to accept. E3 has always acted as a sort of emblematic touchstone in gaming, a big grand showing of what we all do, shouting out to the world that our industry and our work matters. While I’ve seen all manner of defenses of the event and fingers pointed in every direction as to who’s at fault for its dwindling impact, that attachment to E3 does more harm than good in my opinion. As with any major expenditure of funds and effort, in any industry, it needs to carefully and objectively considered. It’s a situation where you have to put aside personal feelings and have a frank discussion about whether attending is actually worthwhile for your business at that time.