One of the first mistakes developers make when handling their own PR is emailing everyone under the sun who writes about games in any capacity. While initially that may seem like a good idea—I see you writing comments like “Isn’t that what you guys do?!”—writers are busy, and a generic pitch that isn’t in line with what they cover is a surefire way to get Marked As Spam and disappear from their inbox forever.

Proper pitch targeting is as simple as finding people who write about games like yours and contacting them, but there’s a lot more to it than that.

Determine Who You Are

The initial part of this is easy: What platform do you work on and what are you making, or what have you made for said platform?

For example, pushing a PC-exclusive title can eliminate all the Mac sites and all the sites that are console-exclusive, meaning that’s thousands of people you don’t have to talk to. Pushing, say, an RPG means you can cut out all the FPS-only sites, the MMO sites, and all the sites with a focus on non-RPG genres. Your to-do list is already significantly smaller.

The second step is determining your identity as a company, which gives you a company voice and style in writing your releases; the tone of your pitches may also need to vary based on the press you’re targeting. Big companies tend to sound very boring and staid because their releases and materials go through 10+ people for approvals–I’m not exaggerating: I still have a chart of the approval process at one of the bigger companies I worked for and, yes, it needed a chart–and come out very bland and corporate.

Smaller companies have a little bit more freedom and flexibility with their voice, but also have the burden of having to win writers over. While Blizzard and Capcom may merit news posts about “Blizzard and Capcom are going to announce something that we don’t know what it is at PAX East!” we find smaller, lesser-known companies struggle to get attention with “Here’s our complete game that we made ourselves,” particularly if their press communications are boring or poorly written.

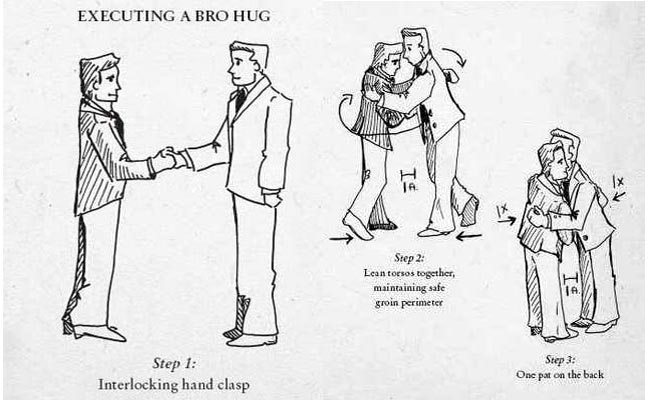

For example, our “voice” as an agency is very casual and informal. I’ve been known to include vaguely relevant Monty Python videos or talk about how grateful we all are for the upcoming weekend rather than stick to a deeply formal voice. Importantly, this isn’t a put-on. We don’t workshop it or critique each other’s causal posts for maximum casual. That’s our personalities and we express ourselves that way in our releases and pretty much everything we do.

Using a casual voice is often quite useful in humanizing you and your company to the media and your audience. However, if your pitch is too casual and chummy, you might come across as unprofessional – generally a no-no when pitching big outlets – while a boring or stiff announcement from an unknown company might alienate a YouTube personality who isn’t quite prepared to read five paragraphs about your business’ achievements. In fact, we specifically include bullets at the top of our press releases with the quick and dirty details expressly for people that don’t have time to read a wall of words.

Here’s some advice on finding your written voice.

Determine What You’re Sending and Who to Talk To

While tempting to bombard the world with your exciting screenshots, you get better results with a more focused pitch.

Before contacting press, determine what you’re sending, as that will influence who you’ll reach out to.

It’s important to remember that media get hundreds of emails a day – many from developers or publishers or agencies looking for coverage – so if you’re sending pitches to the wrong people, your efforts are likely going to waste.

A simple press release, for example, may need to go to a news@ or tips@-type email address, where the site’s multiple news writers rummage through it, looking for the news gems of the day. Emailing a publication’s features editor with a news release they don’t want is a good way to annoy him or her, meaning you don’t get your news posted and you may not be able get a feature posted when you come calling down the road.

Screenshots, videos and other media assets may go to a distinct and separate asset-drop email address rather than the news staff or news@ address, as different teams handle those for some sites. With that said, a release targeted to someone who is interested in the game is much more likely to be successful than one filling up a news@ inbox, since you’ll be competing with literally everyone with news going out that day. As mentioned earlier, while Blizzard and Capcom may merit instant pickup, on a busy news day, you may not. A personalized pitch is much more effective than any blast will ever be.

Sending review and preview builds or code may go to an entirely different editor or may go to the editor in chief or equivalent for handing out to the writing staff, though if you know a writer fancies your sort of game, it can’t hurt to contact them directly.

To begin building your outreach list, start checking potential sites and narrow it down based on that self-profile you created earlier. The ideal find is a masthead, listing everyone on staff with their titles or beats as well as their contact information. Some sites may have their contact information on an About page, but resist the temptation to blast everyone. For sites that covered your previous titles, it’s fairly easy to figure out who to focus on, but for new games, find who has been covering similar games and start with them.

Sometimes, reviewers/writers with an unofficial beat have them because that’s what they get assigned. Sometimes, it’s the area they are deeply passionate about and they’ll be interested in hearing about new ones.

Let me give an example from our work. A client asks us to find an outlet interested in an interview with them for an upcoming real-time strategy game sequel.

The first thing I did was go to the major news sites and find out who had covered the first installment. Of those, I found a couple writers who really enjoyed the first installment, so I’ve already cut down my list of potentials to two really good potential contacts.

The next thing I did was round up those who’d covered the first game if not passionately, then extensively. If they posted a lot of the press releases, nominated it for awards, and otherwise knew the game existed, they went in the next “tier” to approach.

The third level of people to approach would be writers and sites that posted a couple of releases or otherwise covered the first installment in some way. Maybe they weren’t huge fans of the series, but they’d be basically familiar with it and know it existed.

Finally, there’s everyone else that covers that particular platform. While there’s some opportunity here for coverage, because of the writers’ unfamiliarity with this game or genre, they would require a deeper introduction. That’s not to say hold off on pursuing them, but we’ve found coverage from one outlet or a handful of outlets builds a sense of momentum around a game, making it easier to get increasing coverage on a title as that sense of legitimacy builds.

As your time is short, it makes sense to focus on the people who are familiar with your style of game and can help you the most, then branch out into other people who cover the platform and might be interested. Making sure to send the right things–from assets to press releases–to the right people also increases your chance of success.

For games without an existing audience or an easy comparison, things are a little more tricky and require a bit more work. In that instance, it’s worth starting from the platform level and writing to press that cover your platform with an introduction of yourself and your project well before you actually want coverage.

For that, we like to put together a summary of the game, about a paragraph-long description of what it is. Think of the text that would go on the back of a game box. It’s also tremendously helpful to include evidence your game actually exists, like video footage of gameplay or other extensive documentation that your project is more than a great idea.

Be warned that a game that’s hard to describe is going to face a much tougher press reception than one with easily-mapped precursors. Innovation is one of those things everyone says they wants, but if it doesn’t fit the high-concept “It’s like [title] but with

For games that are that hard to explain, a gameplay demo or video is critical. No matter the eloquence of your ideas or rhapsodizing about your concept, a 1 minute gameplay video or short slice-of-gameplay demo can save you days and days of back and forth emails. Consider offering guided tours of the game via either streaming services like Twitch.tv or desktop sharing programs like Skype. These will benefit the press and may even draw curious onlookers that can become customers.

The Brutal Truth About Indie vs. AAA

Part of the targeting process is also audience targeting, not just editor targeting.

Indie developers can get a little starry-eyed imagining that big feature hitting on IGN or GameSpot… something happens here… instant success assured, but the truth of the matter is an unknown indie dev or a more-casual game is going to be hard to place on the bigger sites because they have their own audiences to consider and their audiences have their own tastes.

We have many examples of games where we’ve gotten great coverage at big-name sites, but because it’s not the kind of game their audience will care about, it results in just a few clicks to the game and no sales. By contrast, we’ve seen YouTubers with a few thousand subscribers drive hundreds and even thousands of sales because an obscure, niche, indie game is exactly the reason a lot of their audience tunes in.

Even if you can clear the inbox blockade and make an editor fall in love with your indie title, the audience for their site just may not care. A very mainstream site is going to have gamers that lean towards the mainstream. Making a quirky FPS with retro graphics? They may just compare it to Call of Duty, roll their eyes and move on. Making a small, budget RPG with 20 hours of gameplay and some rough edges? They’ll see it’s not Mass Effect 4 and move on. Then there are games like Facebook games and mobile games where the audience isn’t the usual gamer crowd, so sites are indifferent and their audiences doubly so. Writing about a browser game — even a really good browser game — or a free-to-play game instantly turns off a significant chunk of their audience, even if the game itself is excellent.

Interestingly, a lot of our clients have specifically asked us to focus on sending things as widely as possible rather than working on a “home run”-style exclusive with a bigger site. While a front-page post on a top-tier site may impress executives and investors, the developers we work with that focus more on results than prestige are finding success by working with everyone interested in their game rather than lobbying indifferent but larger sites, even if that means working with YouTubers and streamers and 100 smaller sites rather than 10 big ones. We work with several people that have a Gmail address, a YouTube channel, and maybe a Twitter account, but they have, time and again, driven thousands of dollars in sales while a well-placed article on a major site resulted in only a handful of clicks.

PR Is About Relationships

At its core, PR is about building relationships. When you hire us, or any good PR agency, you’re not hiring a massive database of everyone who writes about video games where we mindlessly send out press releases. What you’re paying for is our knowledge that Destructoid likes this and GameSpot prefers things this way and the news people at Polygon like things done this way while GamesRadar wants things broken down like this.

The gaming press has changed from the days when a massive CCed generic email would get plenty of coverage. Some sites are only interested in video content; some sites will post screenshots in a generic gallery but won’t promote them at all; some specialty sites only cover particular genres or titles; and some sites don’t care how many press releases you send them, they write about what they want when they want.

As you begin sending out emails and talking to people at conventions and shows, you’ll begin accumulating this body of knowledge about who likes what and where to send particular things. If a writer has their AIM address or Skype info in their signature, feel free to add them for quick questions or requests. Don’t abuse it, but use it if you occasionally need to talk to them outside of crowded inboxes.

Twitter is a godsend for PR, both professionals like us and anyone trying to do it themselves. It provides real-time insight into what people are writing about, what issues are hot, and even which writers are looking for new games to play. They will not send out a mass email to their industry contacts asking for a new game to play–which would make all of our lives easier–but they will ask the Twitter masses what they should play this weekend.

Where Twitter helps PR people–be they professional or the guy who drew the short straw at the studio–is that it makes us more human and more interesting and less “that annoying relative that only calls when they want something.” Part of the reason my Twitter feed is a barrage of baseball news and gaming stuff (even, gasp horror, non-client games) is because that’s what I’m genuinely interested in. While it’s less professional-looking than a feed that focuses entirely on client news, it’s considerably more human, and people want to talk to people that share their interests and appear human.

Overall, our job (or yours, if you’re undertaking your own PR) is all about knowing people and what they want, building a relationship that’s mutually beneficial and minimally annoying. No matter how great your game is, remember that it will take a lot of time and a commitment to doing things right – from interacting with press to developing games they love – to raise your company’s profile to the point where every pitch you send out will earn a response, or for media to come to you for coverage. It may take months or years. It may never happen. There are guys we work with and like (and like us!) that we talk to only at shows because otherwise they are drowning in a sea of email.

There’s no sure-fire way to secure media coverage, and it’s exceedingly rare for an unknown developer to rise to fame with their first game. Realize that you’re in it for the long haul and accept that it may be difficult at times. Keep making good games, keep building relationships and don’t burn bridges, and soon enough success will come.

TLDR Tips

- Find your voice as a company

- Find sites that cover your kind of game

- Find sites with the right audience for your kind of game

- Do your research and pitch only those writers and outlets relevant to your story/game

- Working with anyone interested in your game may be more successful than focusing on a high-prestige but indifferent site

- PR is about building relationships and developing a body of knowledge for what writers like and what they’re working on